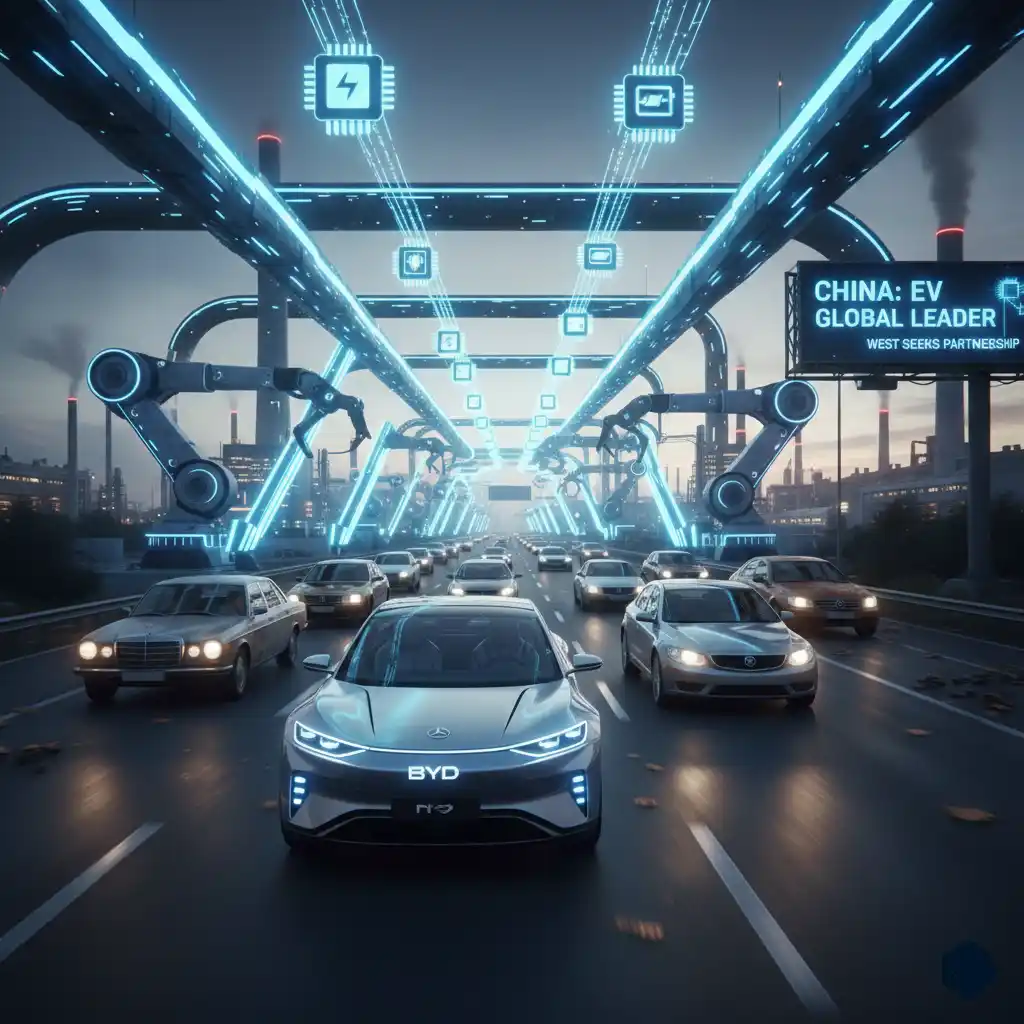

China: From Imitator to Global Leader in the Automotive Industry

The global automotive industry has witnessed a seismic shift, with China emerging as a new superpower. It has moved from being merely a huge market for traditional companies to becoming a key player and a leader in innovation, particularly in the Electric Vehicle (EV) sector. This radical transformation is not accidental; it is the result of a long-term strategy supported by massive investments. Consequently, Western nations that once scoffed at the quality of Chinese cars are now actively seeking partnerships with Beijing to localize production and secure the future of their own industries.

The Rise of Chinese Power and the End of Scorn

For decades, the name “Chinese cars” was associated with poor quality and derivative designs. However, this perception has changed dramatically and rapidly, especially with the global shift towards clean energy. China recognized early on that EVs presented an opportunity for a “technological leap” to bypass the complex traditional engines dominated by the West.

Investment in Technology: Companies like BYD, Geely, and Chery focused on Research and Development (R&D) in crucial areas such as battery technology, artificial intelligence (AI), and integrated software. Modern Chinese cars now offer advanced technology and high quality at competitive prices.

Overtaking the Giants: In 2024, Chinese EV production significantly outperformed the world, with China manufacturing 12.4 million EVs, accounting for over 70% of the global total. Companies like BYD have surpassed their major global competitors in EV sales volume.

Partnerships and Acquisitions: The strategy wasn’t limited to competition. Chinese companies made strategic acquisitions, such as Geely’s purchase of Sweden’s Volvo, leveraging the expertise of these companies to develop their own models.

Strict Control Over Supply Chains

A significant part of China’s dominance lies in its strict control over global supply chains, particularly the core components for electric vehicles:

Rare Earths and Batteries: China controls the most vital parts of the EV value chain, from the extraction and refining of rare earth minerals like lithium, cobalt, and nickel (the fundamental components of batteries) to the production of the batteries themselves. This control provides a massive cost advantage, as Chinese EVs can be up to 53% cheaper than their imported counterparts.

Electronic Chips: Global crises, such as those related to chip shortages at the Chinese-owned Dutch company Nexperia, have demonstrated the fragility of the global automotive industry and its dependence on Chinese electronic components. Disruptions in this supply can paralyze Western production lines.

The West Seeks Partnership: A Strategic Necessity

The West’s view shifted from scorn to concern, and then to recognition of the need for partnership. The goal is no longer merely to compete but to localize production and mitigate total reliance on Beijing.

Securing Supplies: European and American companies are seeking to establish joint ventures and R&D centers within China to access the latest technology and components and ensure a consistent flow of supplies at competitive prices.

Localization and Integration: Chinese companies are no longer just suppliers; they are integrating deeply into foreign markets by establishing Completely Knocked Down (CKD) assembly plants and joint manufacturing projects in regions like the Middle East and Turkey. This represents a strategic shift from pure “export” to “local operation.”

In conclusion, China leveraged the shift to Electric Vehicles to change the game, turning its strategic investments in technology and control over essential resources into a global bargaining power that has made it the indispensable partner for the future of the transportation sector.

Another challenge was time. By the time the SGP Sla 16 was being developed, the war had turned against Germany. Bombings, material shortages, and lack of manpower slowed all high-tech projects. The army shifted its focus toward simpler, faster solutions rather than experimental engines that needed months or years of testing.

Finally, logistics killed the project. An air-cooled diesel X-16 was extremely ambitious, and while it might have performed well if completed, the war simply didn’t leave enough room to finalize, test, and produce it.

You may love to see..

Ford Mustang Dark Horse Review (2025): Specs, Performance, Price & Full Global Analysis

Why Modern Emissions Systems Killed Diesel Reliability

Why AWD Isn’t Always Faster Than RWD in Real-World Driving

Table of Contents