Why Your Car Lies to You: The Hidden Truth Behind Horsepower Numbers

When a manufacturer tells you a car has 300 horsepower, that number doesn’t always mean what you think. In fact, most cars advertise a figure that you will never actually feel on the road. Here’s the simple truth — the number on the brochure is not the power your wheels deliver. It’s a polished, laboratory number.

Crank Horsepower vs Wheel Horsepower

When you see an official horsepower rating, it is almost always crank horsepower (CHP) — measured at the engine before power passes through the transmission, driveshaft, differential, and wheels, but when you actually drive the car, power goes through all these components… and each one steals some of it.

Power Lost on the Way to the Wheels

Every car loses 10–25% of its power depending on:

-

Transmission type (manual, auto, DCT)

-

Drivetrain (FWD, RWD, AWD)

-

Age and wear of parts

For example:

-

A car rated at 300 HP at the crank

-

Might only deliver 240–255 HP to the wheels

That’s a huge difference — and manufacturers know people won’t like seeing the lower number.

Crank HorsePower

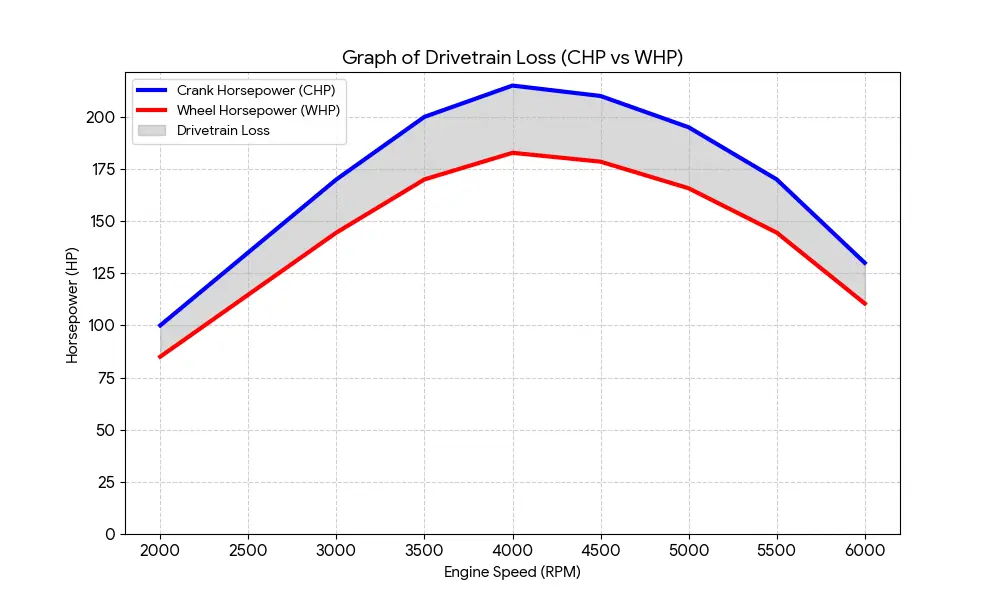

Crank Horsepower (CHP) Curve: This is the higher blue curve, representing the total power the engine produces before it goes through the rest of the car’s drivetrain. This is what manufacturers often advertise.

Wheel HorsePower

Wheel Horsepower (WHP) Curve: This is the lower red curve, representing the actual power measured at the vehicle’s driving wheels.

The shaded grey area between the two curves represents the Drivetrain Loss,

the power lost due to friction in the transmission, driveshaft, and axles.

More about drivetrain

Drivetrain loss is the inevitable reduction in power between what your engine produces at the crankshaft (Crank Horsepower or CHP) and what is actually delivered to the wheels (Wheel Horsepower or WHP).1 This loss occurs because the power must travel through a series of mechanical components that create resistance.2

The power loss is primarily due to two factors: Friction and Rotational Inertia.

Causes of Drivetrain Loss

Causes of Drivetrain Loss

Drivetrain loss is not a fixed number but a dynamic percentage that varies based on vehicle design, fluid temperature, and speed.3 It comes from these main sources:

-

Friction: This is the resistance created by moving parts rubbing against each other, even when lubricated.4 This friction converts power into waste heat.

-

Gears and Bearings: Every gear mesh in the transmission, transfer case, and differential, as well as the bearings supporting the shafts, generates friction.5 More stages of reduction and more bearings mean more loss.

-

Fluid Drag (Windage/Churning): The internal components (gears, shafts, etc.) have to spin through the lubricating oil inside the transmission and differential. This constant stirring and splashing of the fluid requires energy, creating drag, especially at high RPMs and when the oil is cold (thicker).

-

-

Rotational Inertia: This is the energy required to accelerate the mass of the drivetrain components (clutch, flywheel, driveshafts, axles, wheels, and tires). While this loss does not affect the power output at a constant speed, it saps power during acceleration because the engine must constantly use energy to increase the rotational speed of these components.

Loss Based on Drivetrain Type

Loss Based on Drivetrain Type

The most significant factor influencing the magnitude of drivetrain loss is the type of drivetrain system, as it determines the number of components the power must pass through.

| Drivetrain Type | Typical Loss Range | Why the Loss Occurs |

| Front-Wheel Drive (FWD) | 10% – 15% | Shortest and most direct path. The engine and transaxle (transmission and differential combined) are a compact unit mounted near the drive wheels, reducing the number of shafts and gears. |

| Rear-Wheel Drive (RWD) | 15% – 20% | Power must travel through a separate driveshaft (or propeller shaft) and a separate rear differential, adding more weight, friction, and length to the driveline. |

| All-Wheel Drive (AWD/4WD) | 20% – 25%+ | Highest loss due to the most complex system. It includes a transfer case (to split power between axles) and two or more differentials (one for each axle, sometimes a center one), significantly increasing the number of gears, bearings, and rotating mass. |

Table of Contents